Cultural Legacy: The Significance of Uzbek Patterns

Ornaments are folk patterns that adorn artisan objects, architectural structures, clothing and household items, reflecting the centuries-old traditions of the Uzbek people.

By Karomat Gaffarova

It has been said that ornaments are storytellers. The history of ornamentation has its roots in the imagery of nature, flora and fauna, and today, Uzbekistan’s national ornamental styles hold deep, magical meanings that reflect the culture and religion of the people.

Ornaments are found on embroidery, clay, woodcarving, fabric, architecture, jewellery and carpets. In each example, the ornament’s placement takes on significance; for example, it is believed that a knife protects the bearer from evil spirits, while a flowering garden is a symbol of fertility. The cornflower denotes a young man, a red poppy suggests a girl, a tulip means innocence and a rose conjures beauty. Almonds symbolise longevity and pomegranates mean wealth. The ram elicits courage; the nightingale, wisdom.

Each region of the country is distinguished by a separate style of ornamentation with special patterns and weaves. Each also has its own history and meaning.

Suzani ornaments

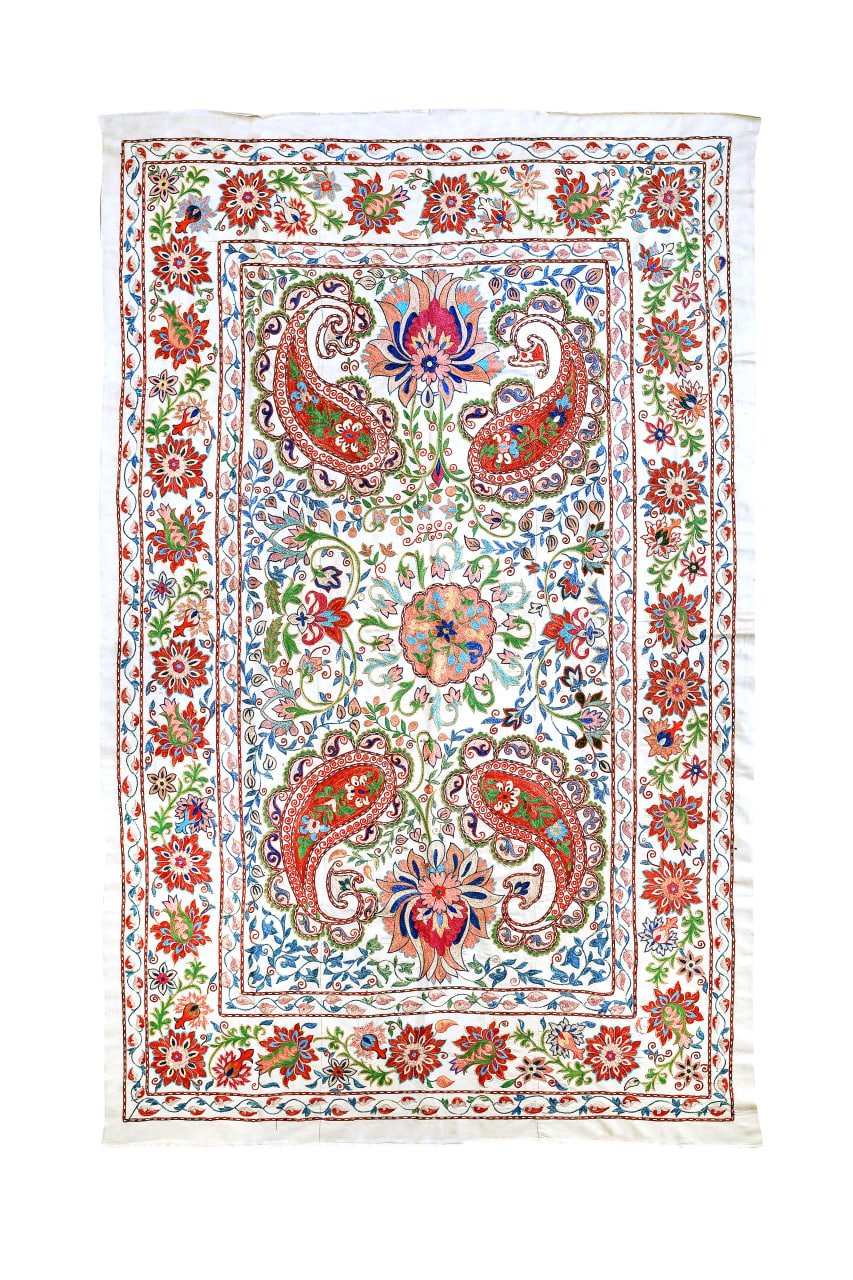

Ornaments are most commonly used in suzani – the traditional embroidered fabrics produced in Uzbekistan and other parts of Central Asia. The word suzani comes from the Persian word suzan, which means needle. Suzanis are used for all sorts of things, from seat cushions to wall decorations, wrappings and prayer mats. They have also become widely popular internationally as decorative elements.

One example of this is found in an article in House & Garden, entitled, “Antique of the week: why every interior should have a suzani”. The author, Jane Audas, writes:

“Textiles impart pattern, warmth and texture to interiors, whether they are simple and understated or colourful and highly decorative. There should be room for both kinds in any space, and if you want to move beyond these and layer in some fantastic, fantastical textiles then a suzani is a wonderful way to do that.”

In the article, textile merchant Susan Deliss discusses the prices and features of suzani, relaying that these needlework pieces traditionally hail from: Tajikistan, Kazakhstan, Afghanistan and Uzbekistan, where most of the good work comes from.

“They were traditionally made by women before they married and then presented to the groom on the wedding day, representing the coming together of two families. A proper antique suzani, from the 19th century, could cost you (probably at auction) upward of £5,000 and nearer £10,000. You would probably hang such a suzani on the wall, should you be lucky enough to have one, as they are valuable enough to be considered as an artwork, and might not stand up to everyday wear and tear if you choose to use them for upholstery.”

The motifs used on suzanis differ depending on where they come from, and even within Uzbekistan, there are a variety of regional styles and ornaments that can relay where the suzani was made. Large flowers, curling leaves, geometric patterns, medallions, stars and moons and even fruits are common motifs.

Thanks to Uzbek artisans, these national ornaments have never lost their relevance and are widely popular even today. Uzbek artisans carefully and faithfully hold the traditions and treasures of ornaments because each one is believed to be the personification of the soul of the people and the bearer of history.

Popular ornamental motifs

Anor Darakhti

The pomegranate ornament is often used in the suzani embroidery of Nurata. The most popular version of the composition is ‘yak mohu, chor shoh’ (four branches, one moon) – an image of a solar or star motif in the centre with flower bushes or bouquets at the corners. Sometimes Nurata embroiders introduce ornaments in inconspicuous places, such as stylised images of birds, animals, humans or household items, calling them the common word ‘surat’ (drawing). This is how the artisans imagined the Garden of Eden – the prototype for gardens of the nobility.

Yulduz Palak

Sometimes called an ‘asterisk’ pattern, this symbol of Tashkent and Pskent is very popular in embroidery. Panels with rosettes containing a star-shaped ornament (‘yulduz’) personify the starry sky and evoke concepts of the cosmos and rotation of the night sky. The term ‘yulduz palak’ literally means ‘starry sky’ – a combination of ‘yulduz’, meaning star and ‘falak’ meaning firmament.

Kalampir Nuskha

The chilli pepper is one of the most common ornaments in Uzbekistan, often used to decorate the national duppi hat. Capsicum is considered a symbol of life, family happiness and a protective talisman to ward off the evil eye.